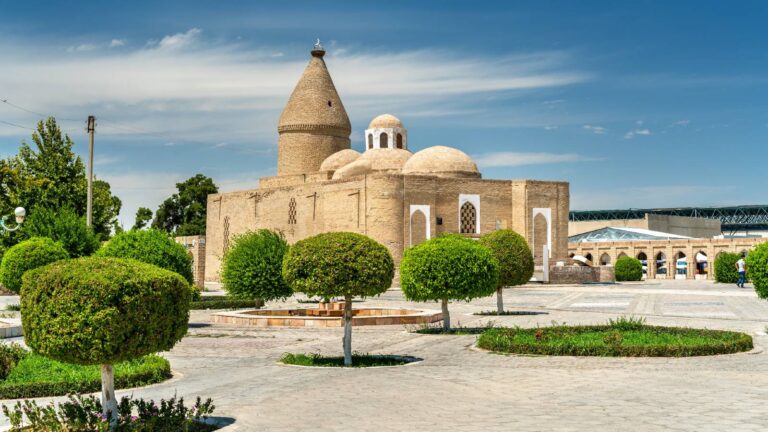

Main image: Ymblanter, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Getting There

Address: Bukhara city, M.Saidjon street, 2

You can get there by taxi and also on foot if you are in Bukhara

Taxi orders work in Bukhara. Numbers: 1054, 1191

What to Expect

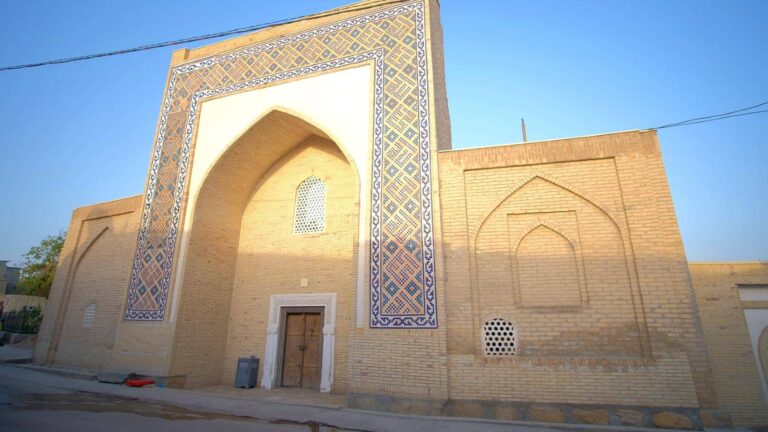

Like all mosques in central Asia, the mosque is organized around an east-west axis canted to the south, toward Mecca, with the qibla wall to the west. The ideal mosque is symmetrical, but the dense urban fabric of 16th century Bukhara likely necessitated a compromise, such that the angle of the building’s south and west facades (facing the street) are out of kilter with the primary axis.

The building’s prayer hall is a spacious domed chamber measuring 9.5 x 9.4 meters, with the dome rising 16 meters overhead with a diameter of 8.2 meters. The main entrance, on the east, includes a deeply recessed chamber crowned with stalactite-like muqarnas vaulting.

A similar treatment is used on the qibla wall to the west, which also incorporates at its heart a smaller but a more subdued mihrab (niche) indicating the direction of Mecca. The chamber’s north and south walls are pierced with a number of doors and windows, some covered by grilles (pandzhara) to attenuate light and prevent entry by birds.

History

The history of the mosque over the subsequent centuries is murky. Badr and Tupev believe the first phase of painting inside the prayer hall probably took place in the late 16th century. It was subsequently redecorated, making extensive use of the kundal technique sometime in the 17th century, possibly between 1641-1660, as the paintings are stylistically similar to those found in Samarkand’s Shir Dor Madrasa and the Tilla Kari.

Coincidentally, both works in Samarkand were sponsored by the wealthy official Yalangtush Bi Alchin, who is known to have resided in Bukhara between the construction of the two monuments. This suggests—but does not prove—that he may have been responsible for the redecoration of the Hoja Zayniddin mosque along similar lines.

Facilities Available

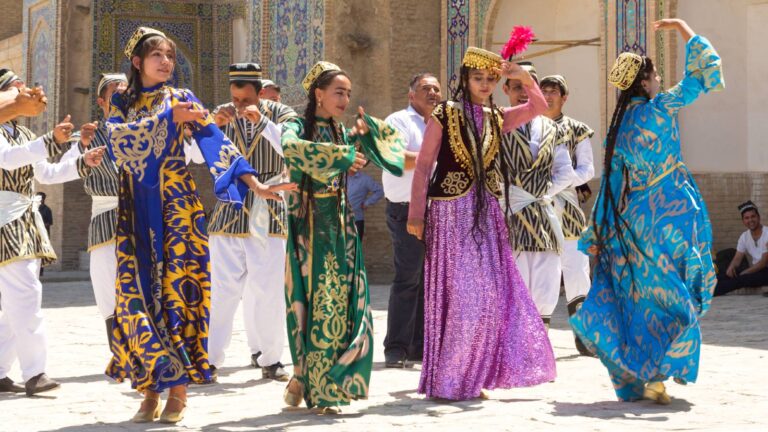

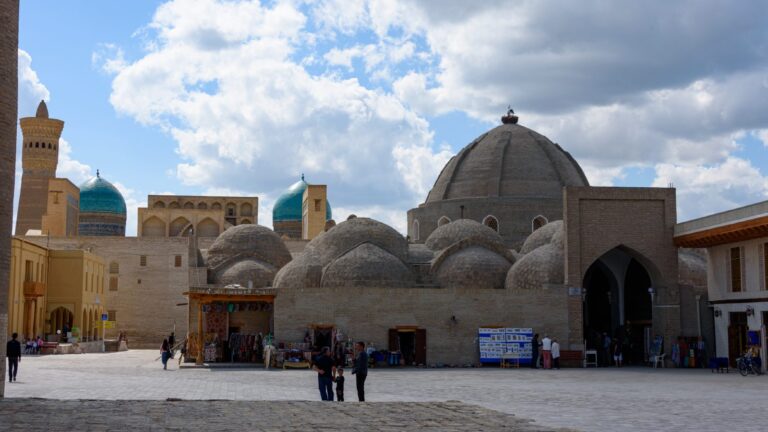

The fusion of a mosque and a khanagha was in fact symbolizing the fusion of classical Islam and Sufism observed during the late medieval period. The complexes of khanaga-mosques usually had several rooms which allowed different functions (mosque, khanagha, madrassah and mazar).

One of the sights of the complex is the tomb of Khodja Zaynuddin previously called “Khodja Turk” which is located in the external niches of the complex in the form of a headstone. The decor of this headstone indicates the canonical traditions of the Koran, in that even governors should be buried not in mausoleums but under the open sky in khazira with brick walls and a small portal.